- Calendar

- Calendar 2026

- March

- Purim

Purim

Purim is one of the most lively and enthusiastic Jewish festivals that will begin at sundown on March 13, 2025, and conclude at sundown on March 14.

It is observed every year on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar that usually falls in the month of February or March on the Gregorian calendar.

With its timeless themes of courage, faith, and unity, Purim invites communities to reflect on their heritage while embracing traditions like reading the Megillah, giving gifts, and rejoicing with festive meals and costumes.

Purim Meaning

The word Purim is the plural form of the Hebrew word pur, which originates from the Akkadian word puru, meaning "lot." This name is tied to the biblical story of Purim as described in the Book of Esther, specifically Esther 3:6–7.

In the story, Haman, an advisor to King Ahasuerus, casts lots (Purim) to determine the date on which he would carry out his plan to destroy the Jewish people. The lot fell on the twelfth month, Adar. This event gives the holiday its name, symbolizing the reversal of fate and the deliverance of the Jewish people.

Purim thus commemorates the triumph over Haman's plot, with themes of survival, community, and celebration of Jewish identity.

What is Purim

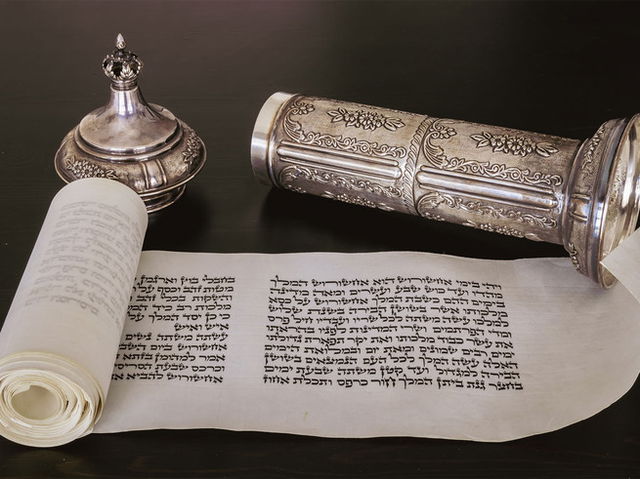

Purim, the Jewish holiday commemorates the events that were described in the Scroll of Esther.

It is a dramatic story that is set over nine years during the Persian Empire revolving around Queen Esther, her cousin Mordecai, and their courage in saving the Jewish people from destruction.

The Story of Purim

The story starts with King Ahasuerus of Persia hosting a lavish six-month feast for his army, nobles, and officials from his vast kingdom of 127 provinces.

This celebration comes to an end with a seven-day feast for the residents of the capital known as Shushan (Susa). Queen Vashti organized a separate drinking feast for the women in the pavilion of the royal courtyard.

During the feast, King Ahasuerus becomes heavily intoxicated and, urged by his courtiers, commands his wife, Vashti, to "display her beauty" before the nobles and the public while wearing her royal crown.

Vashti refuses, embarrassing the king in front of his guests, which leads him to remove her from her position as queen.

To find her replacement, Ahasuerus orders all the beautiful women in the empire to be presented to him.

Among them is Esther, a young Jewish woman who was orphaned at a young age and raised by her cousin Mordecai, a member of the Sanhedrin. Esther gains the king's favor and is chosen as his new queen.

Following Mordecai's advice, she keeps her Jewish identity a secret. Some rabbinic commentators, interpreting specific phrases in the text, suggest that Esther may have actually been Mordecai's wife.

Shortly after, Mordecai uncovers a plot by two palace guards to assassinate the king. He reports this, saving the king's life. The incident is recorded in the royal chronicles but goes unrewarded at the time.

King Ahasuerus appoints Haman as his viceroy.

Haman becomes enraged when Mordecai refuses to bow to him and, upon learning that Mordecai is Jewish, devises a plan to exterminate all Jews in the empire.

He casts lots (called "purim") to determine the date for the massacre, selecting the 14th of the month of Adar.

Haman secures the king's approval and funding for his plan. When Mordecai learns of this, he dons sackcloth and ashes as a sign of mourning and publicly laments.

Many Jews throughout the empire join in fasting and penitence.

Mordecai urges Esther to intervene with the king, even though approaching him without being summoned is punishable by death.

Esther agrees to risk her life by asking Mordecai and the Jewish group to fast and pray for three days. She famously declares, "If I perish, I perish."

On the third day, Esther approaches the king and invites him and Haman to a feast. At this banquet, she invites them to a second feast the following evening.

Meanwhile, Haman, still furious with Mordecai, builds a gallows intending to hang him.

That night, the king suffers from insomnia and asks for the royal chronicles to be read to him. He learns of Mordecai's earlier act of loyalty and realizes that Mordecai was never honored.

The next day, when Haman visits the king to request Mordecai's execution, the king asks Haman how to honor a man deserving of great recognition.

Assuming the honor is for himself, Haman suggests dressing the man in royal robes and parading him on the king’s horse.

To Haman’s horror, the king orders him to do this for Mordecai.

At Esther’s second banquet, she reveals her Jewish identity and exposes Haman’s plot to annihilate her people.

Enraged, the king orders Haman to be hanged on the gallows he built for Mordecai.

But, the decree against the Jews cannot be revoked. Instead, the king allows Mordecai and Esther to issue a new decree permitting the Jews to defend themselves.

On the 13th of Adar, the Jews preemptively strike their enemies, killing 75,000 across the empire, including Haman’s ten sons.

In Shushan, 500 attackers are killed on the first day, and an additional 300 on the next.

Mordecai is appointed second-in-command to the king and establishes Purim as an annual celebration of the Jewish people’s survival.

The Origins and Text of Purim.

The Scroll of Esther which is an essential part of Purim is the final book approved in the Hebrew Bible by the Sages of the Great Assembly.

It dates back to the 4th century BCE and according to the Talmud, it was redacted by the Great Assembly from an original text by Mordechai.

The Tractate Megillah in the Mishnah (c. 200 CE) details the laws of Purim, while the accompanying Tosefta and Gemara (from the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds, redacted around 400 CE and 600 CE) offer further context, including Queen Vashti's connection as Belshazzar's daughter and Esther's royal ancestry, aligning with Josephus' accounts.

The Talmud also discusses related topics, including idolatry linked to Haman in Tractate Sanhedrin and a brief mention of Esther in Tractate Hullin.

The Esther Rabbah, a Midrashic text, has two parts: the first (c. 500 CE) offers commentary on the initial chapters of Esther and influenced the Targum Sheni, while the second, possibly redacted by the 11th century, comments on later chapters and includes material similar to the Josippon, a chronicle of Jewish history.

History of Purim Blended With Other Religions

The story of Purim according to the Jewish historian Josephus in the 1st century CE is based on the Scroll of Esther as told above.

Josephus closely follows the original biblical account but adds some details from the Greek version (called the Septuagint).

For example, he supports the Greek tradition that Ahasuerus, the Persian king in the story, was actually King Artaxerxes.

Josephus even includes the text of the king's letter mentioned in the story and explains how these events fit within the timeline of Ezra and Nehemiah.

He also mentions a period when the Persian Empire persecuted Jews and forced them to worship at Persian shrines.

Centuries later, the Josippon, a Jewish history book written in the 10th century CE, retells the story of Purim in a similar way.

The Josippon follows the Bible's account and adds traditions found in the Greek version and Josephus's writings. However, it leaves out some details about the letters mentioned by Josephus.

The Josippon also adds context about Jewish and Persian history, identifying Darius the Mede as both the uncle and father-in-law of Cyrus the Great.

Islamic historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, in his History of the Prophets and Kings (completed in 915 CE), gives a brief Persian perspective on the story of Purim.

He draws from Jewish and Christian sources, providing unique details such as the original Persian name for Esther, “Asturya.” Al-Tabari places the events during the reign of King Ardashir Bahman (Artaxerxes II) but mistakenly confuses him with Artaxerxes I.

He believes Ahasuerus was a co-ruler alongside Bahman.

Another Islamic historian, Masudi, in The Meadows of Gold (completed in 947 CE), also shares a Persian version of the story.

Masudi describes a Jewish woman who married King Bahman (Artaxerxes II) and saved her people, similar to Esther's role in Jewish tradition.

He also mentions her daughter, Khumay, a figure not found in Jewish texts but well-known in Persian folklore.

Al-Tabari refers to this daughter as Khumani and tells how her father, King Bahman, later married her.

The Persian poet Ferdowsi, in his epic Shahnameh (written around 1000 CE), also recounts this marriage.

Modern biblical scholars generally agree that Ahasuerus in the Book of Esther refers to Xerxes I, a Persian king who ruled from 486 to 465 BCE.

This blend of Jewish, Persian, and Islamic traditions shows how the story of Purim has been understood and retold over centuries, reflecting the cultural influences of the time.

Four Mitzvot of Purim

Purim revolves around four main mitzvot (obligations) that embody its spirit of gratitude, generosity, and celebration:

-

Megillah Reading: The Megillah reading is central to Purim. It is often performed with cantillation, a traditional chant, and includes additional customs like reciting specific verses together and blotting out Haman’s name with noise-making. Women are equally obligated to hear the Megillah, acknowledging their pivotal role in the Purim story.

- Mishloach Manot: The traditions of mishloach manot and matanot la'evyonim highlight the holiday's emphasis on giving. Each person is expected to send at least two types of food to one individual and provide monetary or food donations to two poor people. Charity collections in synagogues ensure that no one is left out of the celebration.

- Matanot La'Evyonim: Giving charity to at least two poor people emphasizes care for the less fortunate.

- Se’udat Purim: The Se’udat Purim is a joyous daytime meal featuring delicious food, wine, and often costumes. While the Talmud encourages celebratory drinking, interpretations of the practice vary, with most authorities advocating moderation to preserve the holiday's joyful and spiritual atmosphere.

- Costumes and Parades: Dressing up in colorful costumes is a hallmark of Purim, symbolizing the hidden miracles in the story of Esther.

- Blotting Out Haman’s Name: With groggers (noise-makers) and stamping feet, congregants symbolically erase the name of the villain Haman during the Megillah reading.

Purim Rituals

Chag Purim Sameach

Purim is marked by joyful greetings exchanged among family and friends. In Hebrew, people say Chag Purim Sameach meaning "Happy Purim Holiday." In Yiddish, the greeting is Ah Freilichin Purim, and in Ladino, it is Purim Allegre, both translating to "Happy Purim."

Masquerading

One of the most beloved customs of Purim is the tradition of wearing costumes and masks. This practice, thought to have originated with Italian Jews in the late 15th century, was influenced by the Roman carnival. It soon spread across Europe and reached the Middle East by the 19th century.

The masquerade symbolizes the hidden nature of the Purim miracle, where divine intervention occurred behind the scenes of seemingly natural events. It also offers anonymity, allowing individuals to give charity without revealing the identity of the recipient.

Other interpretations include:

- Esther hiding her Jewish identity.

- Mordechai's transformation from wearing sackcloth to royal robes.

- The outward act of bowing to Haman while maintaining inner faith.

Burning Haman’s Effigy

Dating back to the 5th century, the burning of Haman’s effigy has been a widespread custom, particularly in regions like Iran and Kurdistan. This tradition, akin to "Guy Fawkes" celebrations, symbolizes the destruction of Haman and is a powerful expression of Purim joy.

Purim Spiel

The Purim spiel is a humorous play recounting the Purim story. Originally from Eastern Europe, these performances have evolved into satirical theatrical shows with music, dance, and comedy. They often include topics beyond the Purim story, bringing laughter and joy to all.

Purim Songs

Music plays an integral role in Purim celebrations, with songs drawn from liturgical, Talmudic, and cultural sources. Popular Purim songs include:

- Mishenichnas Adar ("When Adar enters, joy comes").

- LaYehudim Haitah Orah ("The Jews had light and gladness").

- Shoshanat Yaakov (sung after reading the Megillah).

Children’s songs like Once There Was a Wicked Wicked Man and Ani Purim are also commonly sung, adding a festive atmosphere to the occasion.

Traditional Foods

Purim is celebrated with delicious foods that reflect aspects of the Purim story:

- Hamantaschen: Triangular pastries filled with poppy seeds, fruit jams, or chocolate, symbolizing Haman’s pockets or ears.

- Fazuelos: Fried pastries enjoyed by Sephardic Jews.

- Kreplach: Dumplings with hidden fillings, symbolizing the concealed nature of divine intervention in the Purim story.

- Vegetarian dishes: A nod to Queen Esther's diet of seeds, nuts, and vegetables while maintaining kosher laws in the palace.

Special breads include:

- Ojos de Haman: Moroccan bread symbolizing "Haman's eyes."

- Koilitch: Polish raisin challah, often served during the Purim feast.

Torah Learning

The tradition of Yeshivas Mordechai Hatzadik calls for studying Torah on Purim morning to honor Mordechai, who encouraged Jewish children to engage with the Torah during the Purim story. This practice often includes prizes and treats for children, making it a lively and educational part of the celebration.